Visiting Highgate Cemetery may sound a little strange but I can guarantee you’ll have a fascinating time and will want to return. I’m seriously thinking about becoming a part-time cemetery sleuth.

In the early nineteenth century, London had a huge problem. There was just not enough room for the dead. Deaths were on the rise especially in the overcrowded slums rich with the killer diseases cholera, tuberculosis, diphtheria and typhus. Most of the burial grounds in small parish churches were full to overflowing, and there was just no room to expand. Desperate times called for drastic measures and where used, coffins stacked in 20-foot deep shafts. If they broke up, the poor used them for firewood and unearthed remains left scattered, in full sight. Paupers bodies were just stacked, one on top of the other and if they’d died from a particularly nasty disease lime was spread between them. These were left exposed until the grave was full.

The smell must have been unbearable. Then there was the trade in selling bodies to medical students. Bodysnatchers were employed by Universities to remove fresh corpses, and at the time it was a lucrative business. So, what did the Clergy do? Well, nothing. They overlooked dubious practices because a significant proportion of their generous salary was from burial fees.

Theories flew around, and lobbyists argued that ‘putrid emanations’ from corpses or ‘miasma’ were injurious to health and living.

Anyway, I could write a thesis on the burial practices in London in the early nineteenth century, but instead, I’ll steer you to this fascinating Guardian article instead.

Safe to say, some drastic measures had to be put in place to ensure the dead were treated with some modicum of respect.

Architects lobbied for the creation of suburban cemeteries, but it wasn’t until inspiration from Paris’ Père Lachaise cemetery that reform came about in 1832 when Parliament passed a bill encouraging the establishment of private cemeteries outside London. Over the next decade seven cemeteries were established:

Kensal Green (1832)

West Norwood (1836)

Highgate (1839)

Abney Park (1840)

Nunhead (1840)

Brompton (1840)

Tower Hamlets (1841)

Highgate Cemetery in north London is perhaps the most famous of London’s so-called ‘magnificent seven’. English Heritage has listed it as a Grade 1 Park – both sides of the cemetery – East and West – remain open as active burial grounds with interments taking place on a weekly basis. There are around 170,000 people buried on the site in about 53,000 graves. Fifteen acres were consecrated for those who were Church of England and two acres for Dissenters (everyone else). Rights of burial were granted for a period or in perpetuity. The first inhumation at Highgate Cemetery took place on the 26th May 1839 and was Elizabeth Jackson, a 36-year-old spinster who lived in Little Windmill Street in Soho.

In the day, Highgate Cemetery was landscaped with exotic formal plants which were complemented by the architecture of Geary and Bunning making it THE place to be buried. Cremation wasn’t that fashionable until 1902 when the Cremation Act was passed and Highgate opened their columbarium (cubicles designed to hold urns full of ashes).

There are two chapels for Church of England worshippers and the Dissenters housed in the same building.

As you make your way through the curved paths, you reach a series of ‘death avenues’ which are filled with reminders that the Victorians loved to show off their wealth. Sixteen vaults are fitted with shelves for twelve coffins and were bought by families for their sole use. Through the Avenue, you reach the Circle of Lebanon, complete with a Cedar of Lebanon which includes tombs and mausoleums of some interesting folk. Twenty vaults were originally built on the inner circle, with another sixteen added in the 1870’s.

The Terrace Catacombs are eighty yards wide and hold eight hundred and twenty-five people. There are fifty-five vaults, each with fifteen cavities each.

Some family tombs which cost £5,000 at the time of building would cost £30 million to replicate today. Keep an eye out for the restored vault of Julius Beer, bought after the death of his 8-year-old only daughter, Ada. Here’s what it looks like inside, courtesy of virtual reality, Ada’s serene face is moulded from her Death Mask.

Off the beaten track (and path) we find the graves of the Dickens family. Charles Dickens is buried in Westminster Abbey in Poets’ Corner but his wife, a successful author in her own right, along with her children are buried here.

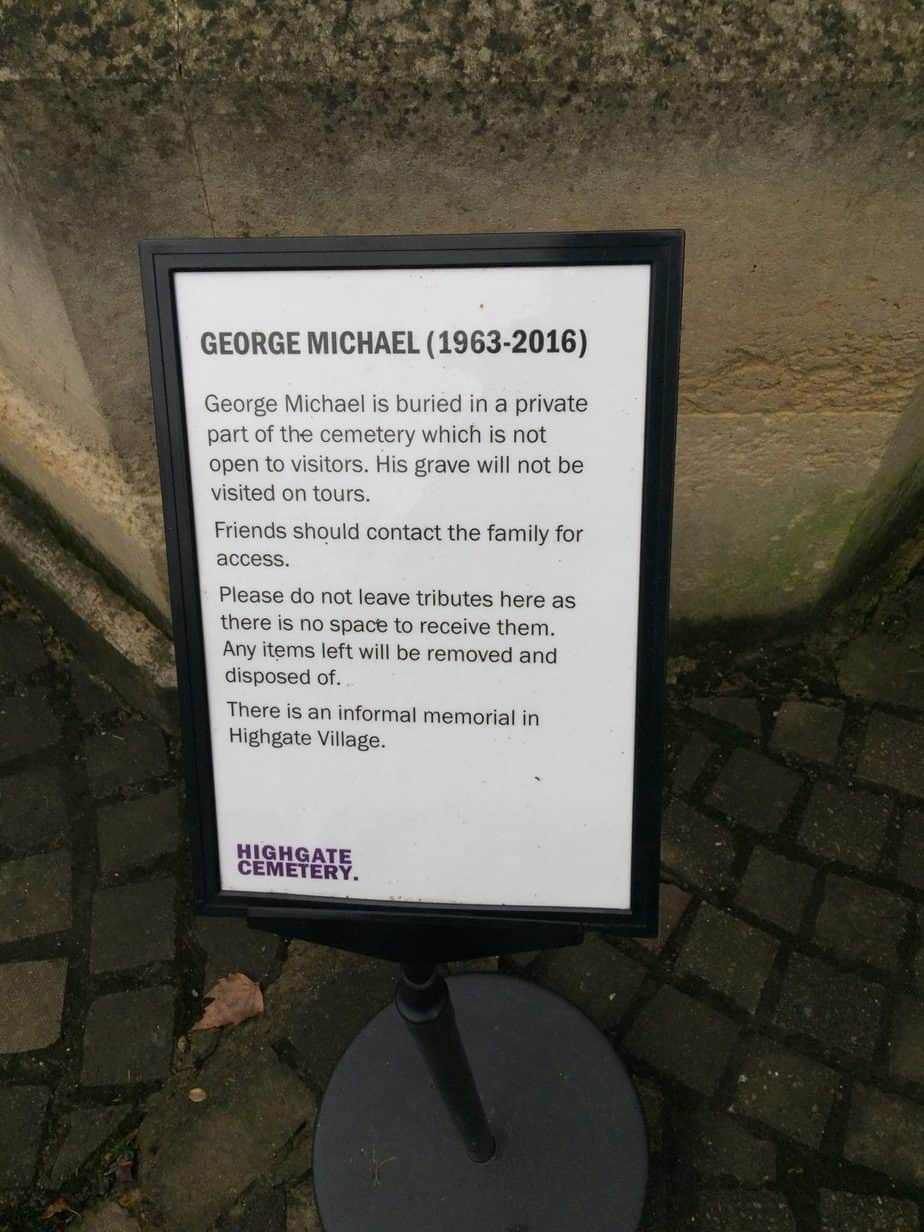

The Russian defector Alexander Litvinenko is buried here, and more recently the pop star George Michael.

Edward Bloor may be familiar to some. Not to me. Yet this architect was responsible for what’s become the focal point for Royal celebration. He designed the Great Facade facing The Mall including the famous balcony on Buckingham Palace, famous for all those Royal photo opportunities we’ve seen over the years.

The inventor of the Faraday cage is buried here in the Dissenter area. He was of the non-conformist Sandemanian faith, formed as the Glasites in Scotland in 1730.

How could I not mention the first TV cooking chef Philip Harben. His programme started in 1946 on the BBC and was broadcast in black and white (obviously). He cooked with his own rations supply and showed people how to eat with what was available at the time.

In 1854 the company extended the cemetery by a further 20 acres on the other side of the Swain’s Lane site. East Cemetery opened two years later. An underground tunnel connects the Chapel with the East and a hydraulic lift, lowered for transportation from one cemetery to the other.

The first burial on the site was of sixteen-year-old Mary-Anne Webster, the daughter of a local baker, on 12 June 1860. It’s here you’ll find Karl Marx, Douglas Adams the author, complete with a pot of pens.

Jeremy Beadle, the TV presenter,’s here, Malcolm McLaren pop impresario is here too, and so is the comedian Max Wall. I adored the headstone of Pop Artist, Patrick Caulfield, no beating about the bush here. No flowery words crafted from lead. Simplicity in itself.

It’s worth getting the map and returning. I was interested to read about Sir Albert Barratt, Director of Barratt and Co Confectioners, who is buried in the East. Now I know that Barratt’s (now Tangerine) make the Sherbert Fountain one of my favourite childhood sweets. A little bit of research and I discover that Barratts had a 5-acre site in Wood Green in North London. Albert was one of the Directors of the company who made everything from my favourite to liquorice allsorts, sweet cigarettes and dolly mixtures. He died in 1941, and although I didn’t get to see his grave, I’m secretly hoping it’s a huge marble Sherbert Fountain. A return visit will surely reveal it’s a giant dolly mixture or most likely a huge red marble edifice.

Bankruptcy

At the turn of the century, elaborate funerals became unfashionable. That, coupled with the outbreak of the Great War may have signalled the beginning of the end but despite losing forty gardeners and groundsmen to conscription, it wasn’t until the thirties when things really began to slide. People moved or died, graves were abandoned, maintenance was paired back and the cemetery began to sell off the property to raise cash. This was the final straw and the company who owned the cemetery was declared bankrupt in 1960. Taken on by another group it limped on for fifteen years when eventually funds ran out and the gates closed. Not even grave owners could get access.

Friends of Highgate Cemetery

If it wasn’t for the Friends of Highgate Cemetery who took up the cause in 1975 who knows what would have happened? They’ve raised thousands of pounds and have restored much in the West Cemetery. It costs £1,000 a day to keep the place running. Graves in the West tend to collapse (marble is heavy, mud slips and slides). Trees fall and Ivy spreads like wildfire, so they charge a fee for a very informative tour.

Tickets cost £12 per person, and our guide was Doreen who not only had an encyclopaedic brain but a fantastic sense of humour.

It’s a very magical place and a beautiful final resting place. In fact, now it seems more nature reserve as the grounds are full of mature trees, shrubbery and plants which provide homes for both birds and wildlife.

Rare inhabitants

Recently, and quite by chance, a rare spider was found in the vaults of Egyptian Avenue. The orb-weaver spider Meta bourneti is the first time the species, which measures more than 30mm, had been recorded in London. Up to 100 spiders were found in the vault which may have been thriving undetected for 150 years. The spiders are ‘cave dwellers’, and the conditions in the vaults mimics the conditions – total darkness in sealed, undisturbed vaults. Some of the tombs where the spider was discovered date back to the 1830s.

Nice to know that in acres of death there’s plenty of life.

For more information on Highgate Cemetery visit their website.

Do take a look at my post on funerary architecture.

Swain’s Lane, Highgate, London N6 6PJ

Nearest tube: Archway then it’s a walk-up Highgate Hill (this is closer than Highgate tube)