Sparkling sake – soft, sweet and with a unique delicate flavour – just one of the sake’s I tried at the Japanese Embassy when I was invited for a sake and food pairing event ahead of Hyper Japan‘s The Eat Japan Sake Experience.

Sparkling sake is a perfect accompaniment to sushi, sashimi and tempura and when served ice-cold is delicious. One of my favourites was the low-alcohol MIO Sparkling Sake which is very gently carbonated and perfect as an introduction to this drink. Ideal for a hot summer evening and perfect to serve with a light dessert course. Natsuki Kiuya is the former Head Sommelier at ROKA and ZUMA and is the founder of the ‘Museum of Sake‘ – a PR agency and website promoting the delights of sake. She comes from a family of sake brewers from the Akita prefecture in Japan.

She talks us through the basic sake making process and classification which gets me wanting to know more. Sake is a little like making beer in terms of the chemical process, although sake uses the one process of starch breakdown and yeast fermentation. This results in an alcohol content of more than 18% by volume.

Table rice can be used to make sake but a special type of rice called sakamai is used for large-scale sake production. Removing everything from the rice kernel, but the starch, preserves the purity of the flavour.

To make sense of the slide ‘Junmai’ (rice, koji and yeast are used) and ‘Non-Junmai’ (rice, koji, yeast and distilled alcohol). The categories are then broken down into how much the rice grain is milled.

From Junmai Daiginjo has at least 50% 50% of the original grain polished away. A fine example of the skill of the brewmaster using labour intensive, traditional tools and methods. To Futsushu (table sake) the rice has been milled (polished) less than 70% which means that 30% of the outer shell remains. This is reasonably priced and accounts for 70% of the Japanese sake market. A hot, classic style. Table rice could be used for cheaper versions. Alcohol will be added in more amounts than allowed in Honjozo. Sanzoshu (triple sake) is at the bottom of the triangle and adds enough alcohol to triple the batch yield. Sugars and organic acids will also be added.

Brewing sake uses a high volume of water – from washing and steaming the rice, as well as the fermentation stage and cleaning the tanks. Japan has exhaustive access to water from the river, sea and mountains and there are several areas where the water is of the highest quality. Sake breweries tend to open near the best source of water and like the UK they have issues with hard and soft water. Semi-hard water is believed to be the best for sake making and that’s found in the Nada region and along with Fushimi, it produces 45% of all the sake in Japan. Hard water, or kosui, whilst rich in minerals makes the sake dry and bold in flavour. Soft water, or nansui, results in a softer, more feminine style known as Fushimizu in Kyoto region.

Once the rice and water have been sourced, you can begin to brew sake. Rice is treated and milled. The rice is washed and soaked. The rice is steamed to breakdown the starch, then laid out on trays so it cools quickly, allowing the surface dry out slight The steamed rice is sprayed with spores of the koji mold and put into a koji-making machine. After about 40 hours it is taken out as koji. During the process, the temperature is automatically adjusted and kept at 38 to 40°C (100-104°F). Steamed rice, koji, water and the yeast (moto) is added – there are 15 common strains – numbers 7, 9 and 10 being the most used in sake brewing. The brewing process happens at low temperatures in open tanks and takes about 20-35 days to complete. Brewing in cold weather prevents the chances of contamination by airborne microbes. No more ingredients are added to the brewing process, the character of the sake depends entirely on the choice of yeast, and the fermentation process – temperature, oxygen levels, tank size.

From this mixture comes the Moromi which looks like thick porridge. It’s poured into tubes made of fabric and then pressed. Clear Sake is pressed out of fine fabric and is bottled and the sake lees (Kasu) stays in the bags. It’s used in Japanese Cooking, pickling vegetables and is used in beauty products. The Clear sake is called Nama (living) as it still has live yeast and active enzymes present. This sake has to be refrigerated until it’s ready to drink. Sake is pasteurised, quickly heated to 62C and then cooled rapidly before bottling. The pasteurisation process stops the yeast and enzymes in their tracks, giving the sake a longer shelf life that doesn’t need refrigeration. In terms of keeping Sake it’s not aged for very long, usually about 6 months to 1 year.

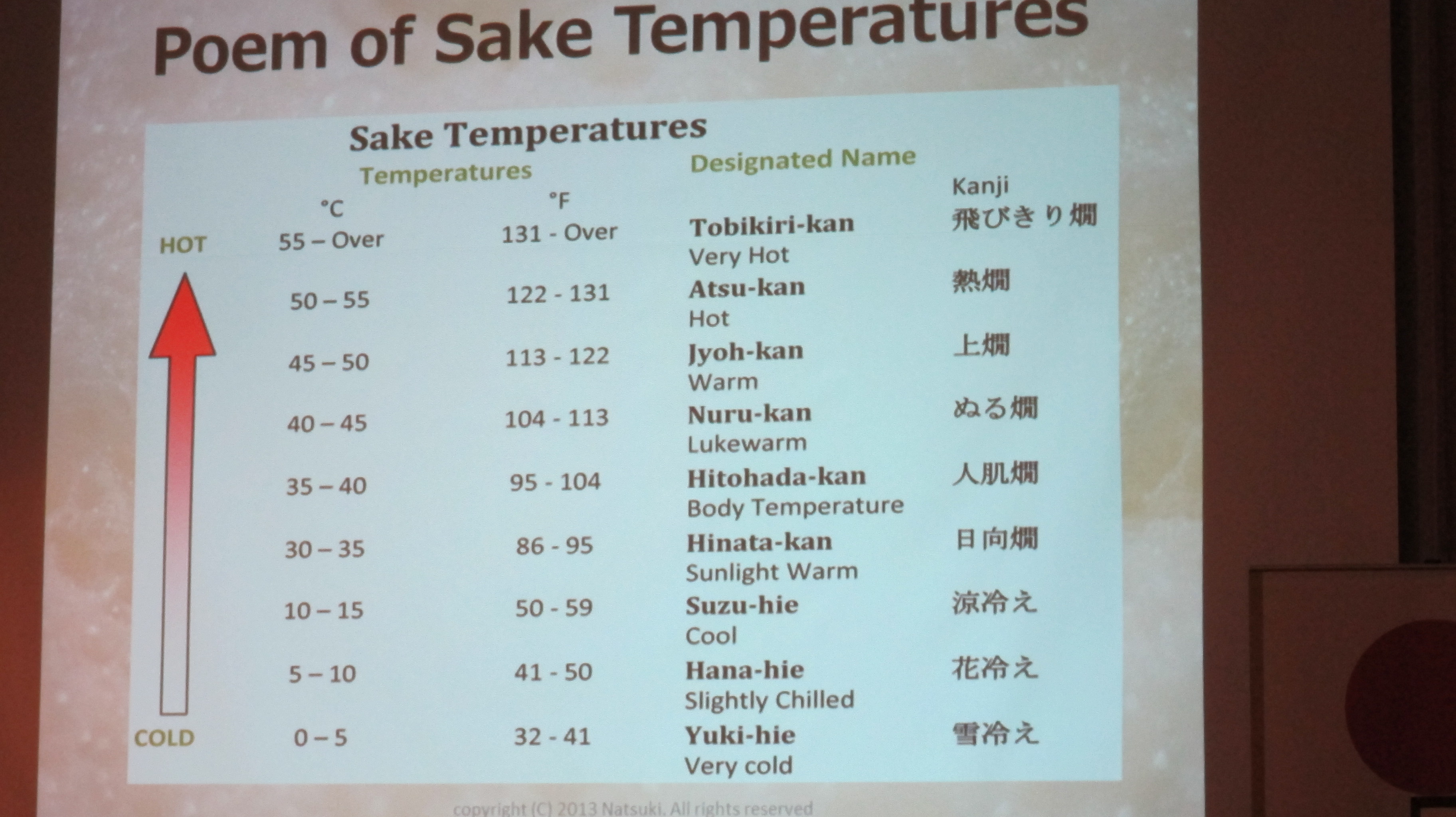

Sake temperature is key to the flavour – some, like the sparkling sake are sold ice cold, whilst others need to be heated. The glassware or stoneware drinking vessel will change too.

We were introduced to a few different types of sake by Natsuki and some dishes which had been made by the talented Akemi Yokoyama from Sozai – the first cookery school in the UK dedicated to teaching students how to make Japanese dishes. You could say she’s simply the best. Growing up in Sapporo she enjoyed foraging for food which has given her a great understanding of why it’s important to usie the freshest, highest quality ingredients. Akemi came to London in 1985, where she learned sushi making while working in London’s popular Japanese restaurant Hiroko. She was hired four years later to work for the singer Tina Turner as her private chef here in the capital.

To ease us in gently we began with a premium sparkling sake ‘Suzune Wabi’ produced by Ichinokura which is ideal for serving with seafood. The rice polish ratio of this was 65% and the alcohol was low at 5%, best served chilled.

With it we had a deep-fried marinated flatfish with Myo-ga which is sitting on top of the battered fish. Myo-ga is believed to make you forgetful (but this is simply a myth). It’s a Japanese ginger sold in China and certain parts of Korea as well and is used as a garnish, can be pickled or battered for tempura. It’s like very young sugar cane in that it’s delicately sweet with a very subtle ginger flavour.

The next sake was White Label ‘Hakuryu Daiginjo” produced by Yoshida Brewing in Hakuryu a robust sake where half of the rice has been removed before the sake is made, again this is served chilled. This smelt of orchard fruits – green apple with hints of mango and tropical fruits. The acidity is good with creamy textures of coconut. This is great served with lamb and mint sauce or grilled aubergine and miso.

We had a chicken meatballs dish with a hatcho miso sauce and sansho pepper.

Hatcho miso is highly regional and there are hundreds of different types – the four main are white, red, mixed miso and hatcho. It’s dark and intense with a slight bitterness. It’s usually painted onto aubergine and is made from soya beans only. It’s aged for a minimum of 2 years. The use of miso is limitless, it can be used to thicken sauces, great in salads, pasta sauces and fabulous on meat dishes.

Sansho pepper will be familiar to those who have eaten broiled eel on a bed of rice with teriyaki sauce. Often powder is sprinkled on top of the dish and that is sansho pepper in powder form. It’s closely related to Sezchuan Pepper. It’s not hot or pungent at all but has a lemon-flavour with a tingly sensation. It transforms a dull miso soup. The sansho pepper is in corn form on top of the hatcho miso.

Lucky me. More Wagyu Beef but this time a fillet with Shio-koji. You may have picked up that Shio-koji is the grains that are used to create the moss on the cooked rice to make sake.

This was served with Manabito Ginjo by Hinomaru Jozo a clean and fresh sake which was very light and refreshing. It has strong acidity and a zesty grapefruit and lime palate which develops into a creamy nutty flavour. Good with Caesar salad or a seared salmon.

The next sake was paired with a stuffed squid with rice dish, garnished with cherry blossom. Kimoto Junmai produced by Sho Chiku Bai Shirabegura was sweet and can be served chilled, at room temperature or warm. We were served it warm in a small stone cup.

The cherry blossom is picked at springtime in bunches of 3 or 4, they’re salted and pickled in vinegar which helps to keep their beautiful pink colour. These are traditionally served in tea at a celebration (usually marriage ceremonies) and they compliment delicate food from sushi, clear broth or added to bread.

The cherry blossoms are refreshed in water to remove the salt.

Pickled Japanese plums have an acquired taste – acidic and salty but with a wonderful fruitiness – they’re good for cooking and a fantastic ingredient.

Japanese housewives will be picking plums just about now to stone and salt, pickling in a Japanese liqueur. They’re aged and pickled for about a month and then sundried. They’re eaten with rice and a popular dish using these is pickled plum, squid and sansho leaves. Apparently this is a favourite of Elvis Costelloe who we’re told speaks fluent Japanese (he was a regular to Hiroko when Akemi was a chef there).

Our final dish was a tofu cheesecake which was light and full of flavour it was served with Umeboshi Pickles and Apricot Puree. This was served with a plum liqueur which is best served on the rocks. It was slightly warm but nonetheless the Umenoyado Aragoshi Umeshu again from the Umenoyado Brewery was delicious. Ume plums are harvested and matured in sake and sugar, then grated and blended, the pulp is clearly visible in the glass. The liqueur is on the right side of sweet and delicious as an aperitif or with dessert.

A great couple of hours learning the basics about sake from Natsuki and that there’s more to Japanese food than sushi from Akemi. Thanks to both.

Hyper Japan begins on Friday 25th and continues until Sunday 27th at Earls Court Exhibition Centre. Tickets cost £12 in advance or £15 on the door. To take part in The Eat-Japan Sake Experience (a little like my experience) it will cost an extra £15.